Champagne is a place located in the north-east of France, a little over two-hour drive east from Paris. The wine produced here is called, guess what, Champagne, mostly sparkling, with a small amount of still wine.

Table of Contents

All began with an accident

The earliest champagne hundreds of years ago was a fizz. What the winemakers intended to make was actually a still wine. The grapes were harvested and made into wine in the autumn. Everything was fine over the winter till the spring when the temperatures rose and the dead yeast in the bottle came back to life to restart fermentation. The CO2 produced in this process formed bubbles in the bottles. These bubbles were a headache for the winemakers, who considered fizzy champagne a failure. But for consumers across the Channel, it was perfect. Fizzy Champagne was adored in England.

Later, the practice of adding a mixture of sugar and yeast (liqueur de tirage) into the bottle was developed as the second fermentation. The added mixture produced more bubbles than the resurrecting yeast in the spring, so Champagne went from being fizzy to fully sparkling. A larger number of bubbles meant the pressure inside the bottle was also higher. If the original glass bottle was still used, the pressure would break through the bottle from the inside and cause a tragedy. For this reason, the bottle was later changed to a thicker, heavier one for this new style Champagne. If you weighed an empty bottle of a Champagne and an empty one of a still wine, you’d see the difference.

Label writes what?

The information on the label of a bottle of Champagne is a good indicator of the style of the bottle:

- Non Vintage (NV): Several vintages of base wine are blended and 2nd fermented in the bottle (see How is Wine Made(2) for Champagne making). In some years, due to poor climatic conditions, the low grape yield leads to not enough wine being made; blending multiple vintages can solve this problem.

- Vintage: Made from base wine of a single vintage, usually produced only in the best years.

- Rosé: Either from a blend of red and white base wines or from the byproduct of red winemaking, in which some liquid produced during grape crushing is removed to concentrate the juice for making red wine; the removed liquid has a pink tint, ideal for rosé making (see How is Wine Made for red winemaking)

- Blanc de Blancs: Made from 100% green grapes, such as Chardonny

- Blanc de Noirs: Made from 100% black grapes, e.g. Pinot Noir or Meunier (when fermented skin-off, the colour of the final wine will be pale like white wine)

- Grand Cru: Made from grapes grown in villages classified as Grand Cru (there are 17 Grand Cru Champagne villages)

- Premier Cru: Made from grapes grown in villages classified as Premier Cru (44 Premier Cru Champagne villages)

- Prestige Cuvée: The best quality base wines from different batches are blended and 2nd fermented in the bottle

- AOC Rosé des Riceys or AOC Coteaux Champenois on the label tells you it’s a still Champagne

The Disliked Meunier

Of the 7 permitted grape varieties for Champagne making, the most common are Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Meunier. The first two varieties are very well known and loved in winemaking, while Meunier is much less so that if a Champagne uses Meunier grown in a Premier Cru or a Grand Cru, its label cannot write Grand Cru or Premier Cru. The Champagne regulation body Comité Champagne certainly has its favourites!

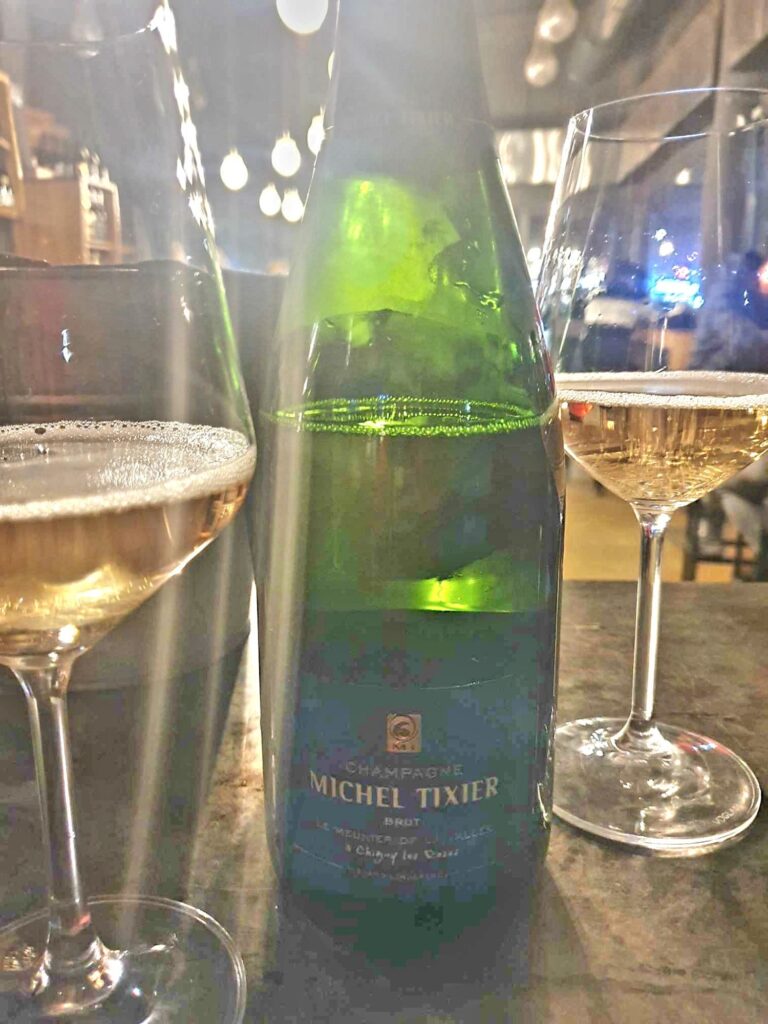

In November last year, at El Büscia, a sparkling wine bar in Milan, I tasted my first 100% Meunier Champagne, made by Michel Tixier. It had an intense nutty aroma and flavour, very different from those made from Chardonnay or Pinot Noir. A “nice for a change” Champagne. This wine was made from Meunier grapes grown in a Premier Cru village called Chigny-les-Roses, for Meunier’s sake on the label there was no mention of Premier Cru. The winery could’ve pulled up all the Meunier and replaced with Pinot Noir or Chardonnay for the label to be more appealing to the market, but there must’ve been a reason why they didn’t do it.

Grower to House

There are three main types of Champagne producers:

- Grower (Récoltant manipulant in French; RM may show on the label)

- Co-operative (Coopérative de manipulation in French, CM on the label)

- House (Négociant manipulant in French; NM on the label)

A grower grows their own grapes and makes their own wine; a co-operative uses grapes grown by its members (who are growers) to make wine under the co-operative’s brand; a Champagne house buys grapes from growers to make wine and sells it under its own brand.

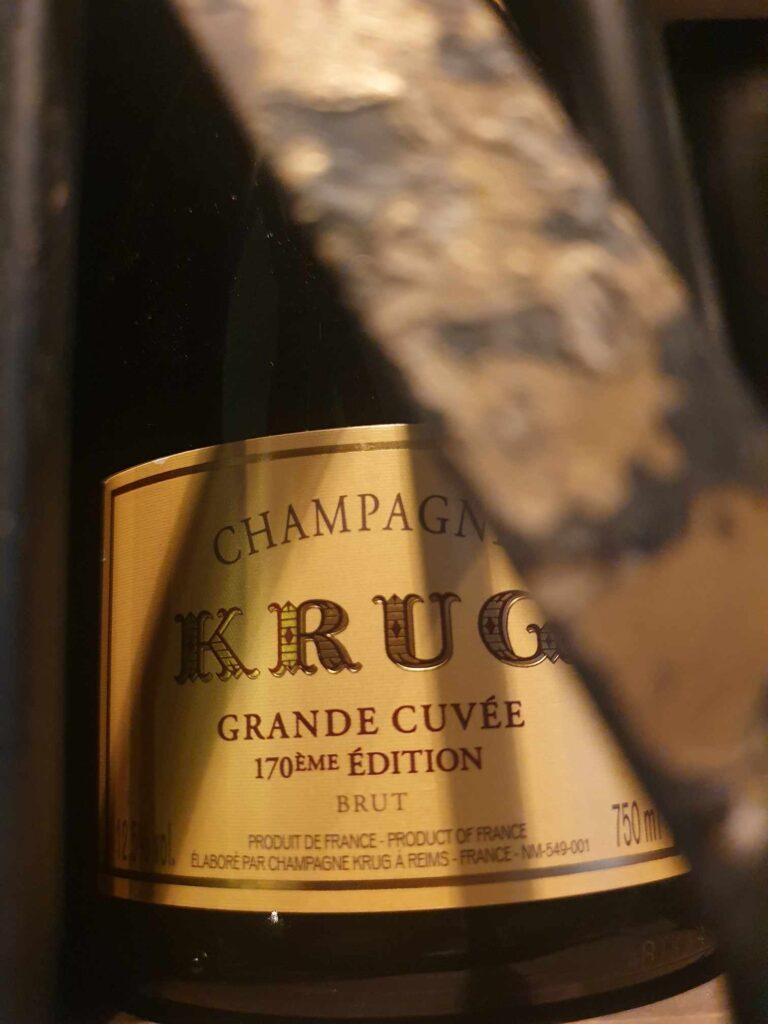

In terms of volume, the house produces the most Champagne, followed by the grower, and then the co-operative. Well-known houses such as Moët & Chandon, Dom Pérignon and Krug are now part of the luxury goods group LVMH, making these house Champagne “conglomerate Champagne”.

Conglomerate Champagne brands are well known and look nice when being given as a present, but you may need to go for the more expensive end of a brand’s product range to get to taste a Champagne of excellent quality. The basic ones are usually quite forgettable. Grower and co-operative Champagnes offer better value for money, but the downside is that there are so many of them that it can be difficult to know where to start. If you know of a wine shop that you trust, ask the salesperson for grower Champagne advice. You could also attend a grower Champagne wine fair. After tasting a few, you’ll know which grower Champagne you prefer.