Two months ago in Taipei, I was talking to a wine bar owner about natural wine.

“In my opinion, most people drinking natural wine in Taiwan are just trend followers who know absolutely nothing about what they’re drinking,” so he said.

One may well take these words as a criticism, interpreting that whoever goes for these non-traditional wines is no serious taster.

But I, for one, choose to see this statement in an entirely different way.

For natural wine consumers to be trend followers means first of all natural wine has indeed initiated a trend. Modern wine industry has been so developed that for now almost zero trend in wine could seem new or exciting. And the fact that the trend of natural wine, depicting a refreshing image about wine like never before, is followed by many should be deemed great news for an industry seeing sales decline year by year. After all, any chance wine has in the face of gin, sake, beer or whisky if it continues to look and feel like last millemium?

Then what about consumers knowing absolutely nothing about what they’re drinking? Is this really such a big deal?

If you asked me, I’d say there’s no other way of tasting natural wine but knowing nothing about it. On tasting Dario Prinčič’s Sivi, a ramato made from Pinot Grigio, the flavours I sensed were plum, quince, hawthorn, herbs, peppercorn and tea, nothing like the peach, pear or melon you’d usually taste in a Pinot Grigio. In a way, tasting this natural Pinot Grigio wine has freed me from the shackles of varietal characteristics.

One more example. Daniele Ricci’s 90-day skin macerating Il Giallo di Costa has transformed the ripe peach, floral and mineral notes common in a Timorasso into a rather different profile of dried apricot and candied orange. When one can’t tell the variety to be Timorasso, one certainly can’t tell that the wine hails from Colli tortonesi, in northwestern Italy, the only wine region on earth featuring Timorasso.

Not being able to make any knowledgeable judgement about the aromas or the flavours based on the variety or the place of origin, consumers can just focus on what is being sensed on the nose and the palate as they taste the wine and decide if they like it. And this, is exactly what most people’s relationship with beer and whisky is like.

In Taiwan, when I ask someone if they drink wine, I’m often told, “I do, but since I don’t know much about it, I drink more whisky.”

The implication here is that you need to know a good deal about wine to drink it, but the same does not apply to whisky (I believe that nine out of ten people who answer me this way do not drink whisky because they’ve obtained a certificate on whisky tasting), nor to beer.

No need to know anything about what you’re drinking is precisely the reason why beer and whisky are the two best-selling alcoholic beverages in Taiwan.

On the other hand, a common scenario for many prospect wine drinkers would be: they pop into a supermarket with a simple hope of bringing home a bottle of wine they may like. But as soon as they enter the aisle where they are bombarded with impossible-to-pronounce, enigmatic names, varieties, regions or sub-regions, they flee to the next aisle without looking back, grab six beers and leave.

While wine’s innate and difficult-to-shake-off “sense of barrier and ritual” can be fascinating, it also makes it fatally challenging for wine to attract a wider clientele.

Fortunately, the sense of barrier and ritual needs not go hand in hand with natural wines.

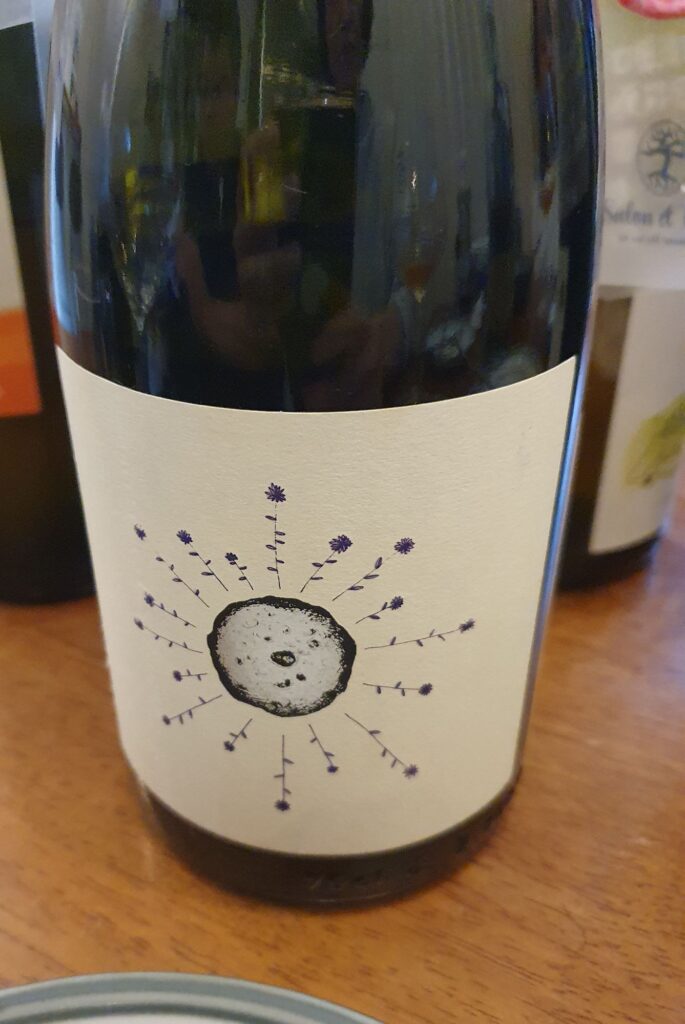

In the world of natural wine, a wine’s variety or place of origin matters no more, as long as the label appeals to you, you give it a try, and you decide if the wine is good or not. This perfectly explains why natural wine’s labels are usually either utterly dazzlingly colourful or unforgivably minimalist, both to attract attention.

Whether the traditionalists like it or not, the philosophy, led by natural wine, of drinking wine like beer and whisky is revitalising the global wine industry.

More on natural wine:🎬What is Natural Wine?